January 2026 marked a new chapter in Indonesia’s criminal justice system. The new Criminal Code has officially come into force, along with the Law on the Adjustment of Criminal Provisions. Among the many changes introduced, abortion is included as one of the key legal “reforms.”

Under Article 463(2) of the new Criminal Code, abortion is allowed in only two situations: when a pregnancy results from sexual violence and is under 14 weeks, or when the pregnancy involves a medical emergency. The law also allows for the provision of abortion medication in these limited cases.

The government has described these changes as progress. But in reality, they are not enough.

The new law still treats abortion as a crime, not as healthcare.

Abortion remains broadly prohibited, with only narrow exceptions that are difficult, if not impossible, to access in practice. Instead of recognizing abortion as part of essential public health services, the state continues to rely on punishment and criminal control.

On paper, existing laws allow abortion in limited cases. In practice, access remains unclear. The Ministry of Health has not designated healthcare facilities authorized to provide safe abortion services. As a result, the legal exceptions offered by the new Criminal Code and the Health Law exist mostly in theory, not in real life.

Even worse, the changes may make access more difficult than before. Abortion services are limited to advanced healthcare facilities and can only be provided by obstetrics and gynaecology specialists. Survivors of sexual violence must also obtain documentation from law enforcement. These requirements delay care, increase stigma, and place survivors under unnecessary pressure. For many, they function as barriers, not safeguards.

This approach ignores the reality faced by millions in Indonesia.

Unintended pregnancy remains common. These pregnancies are not simply the result of “individual choices,” but of structural failures: limited access to contraception, weak sexual and reproductive health education, and inadequate services for survivors of sexual violence.

Sexual violence itself remains widespread. Between 2018 and 2023, Komnas Perempuan recorded 103 reported rape cases resulting in unintended pregnancies. For survivors, pregnancy can be a continuation of trauma. Forcing people to carry pregnancies to term, or to navigate complex legal hurdles to access abortion is not protection. It is harm.

The consequences are visible beyond pregnancy itself. In 2024, Statistics Indonesia (BPS) reported that 4.58% of children under five experience inadequate care, an increase from previous years. This shows how forced continuation of unintended pregnancies can lead to situations where children are raised without sufficient support. At the same time, maternal mortality remains alarmingly high, with 4,129 maternal deaths recorded in 2023. These are not abstract numbers, they reflect preventable loss of life.

Indonesia has yet to build a system that supports safe abortion as part of reproductive justice.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has long stated that abortion is essential healthcare. WHO also recommends mifepristone and misoprostol as safe and effective abortion medications. These methods significantly reduce complications and maternal deaths. Yet Indonesia still bans the circulation of mifepristone and continues to prioritize criminalization over care.

Global evidence is clear: banning abortion does not stop unintended pregnancies. The World Health Organization estimates that around 45% of abortions worldwide are unsafe, mostly in developing countries. Indonesia is no exception. Restrictive laws create unequal access, those with money can find safer options, while poorer and marginalized people face health risks and criminal charges. In this system, the law does not protect life. It protects privilege.

If Indonesia is serious about reproductive justice, legal reform must go further.

Abortion must be decriminalized. Administrative barriers must be removed. Primary healthcare facilities and general practitioners must be allowed to provide care. Safe abortion medications must be made available in line with WHO guidance.

Without these changes, the new abortion provisions in the Criminal Code are little more than symbolic. They do not save lives. They do not protect survivors. And they do not ensure dignity. What Indonesia needs is not partial reform, but real political will to treat reproductive health as a matter of justice, not as a crime.

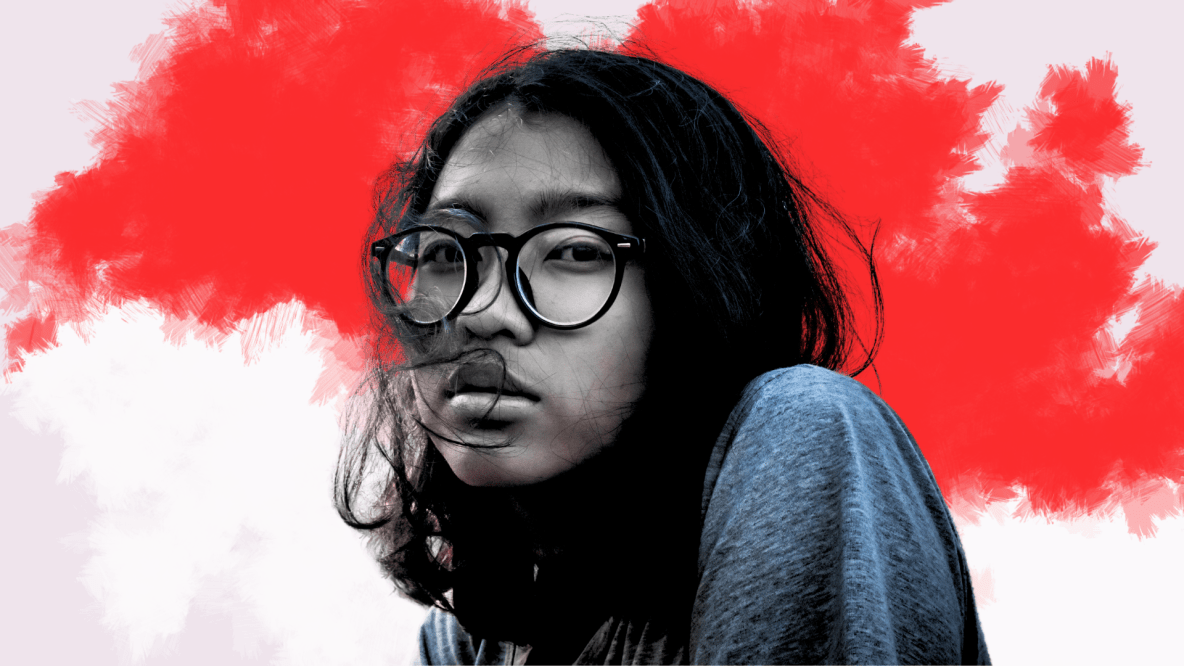

By Maidina Rahmawati, Deputy Director at the Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, a SAAF grantee partner in Indonesia.